Industrial Concentration in the U.S. Economy is Declining, Not Increasing

Story by U.S. Chamber of Commerce

Industrial concentration has been declining rather than increasing since 2007, according to a new study conducted by NERA Economic Consulting and commissioned by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Using the most up-to-date economic census data available, “Industrial Concentration in the United States 2002 – 2017,” debunks the misguided notion that the U.S. economy is plagued by rising and excessive levels of industrial concentration.

“Many of the assumptions regarding industrial concentration that are currently steering public debates around mergers and acquisitions, antitrust, and regulation lack empirical evidence,” said Neil Bradley, Executive Vice President and Chief Policy Officer, U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “This data sets the record straight. America is home to the most vibrant and dynamic economy thanks to vigorous competition in the marketplace, which continues to spur new ideas and provide innovative products and services to consumers.”

In the study, Dr. Robert Kulick, Associate Director, NERA Economic Consulting, evaluates three key questions surrounding the debate about industrial concentration in the U.S. economy: (1) is industrial concentration rising? (2) is industrial concentration persistent? (3) is industrial concentration economically harmful?

The study revealed the following trends:

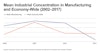

- Industrial concentration has been declining rather than increasing. Concentration in the manufacturing sector and economy-wide concentration have both been declining since 2007. * Average concentration in the U.S. economy declined by approximately two percent from 2007 to 2017.

- Levels of industrial concentration in the U.S. economy fluctuate over time. Higher concentration industries tend to become less concentrated while lower concentration industries tend to become more concentrated. For example, for the most concentrated industries in 2002, average concentration fell by approximately eight percentage points, while concentration rose by over three percentage points for the least concentrated industries. This suggests that trends in concentration are influenced by transient economic shocks that dissipate in future periods.

- Rising industrial concentration is often a sign of increasing market competition and associated with positive outcomes such as output growth, job creation, and higher employee compensation. For example, the taxi service industry demonstrates the strong relationship between rising industrial concentration and increasing market competition. Industrial concentration exploded in the taxi service industry from 2002 to 2017, increasing by 59.6 percent, while output increased by over 650 percent. The substantial increase in concentration occurred between 2012 and 2017, corresponding to the emergence of a new disruptive technology: ride-hailing platforms. Uber’s “UberX” service debuted in July 2012, and Lyft entered the market in August 2012. Economic research has shown that the emergence of ride-hailing services increased competition. Thus, the substantial increase in industrial concentration associated with the taxi service industry was the direct result of new entry into the market.

Bradley concluded, “Concentration is a myth that underpins the administration’s executive order on competition, its narrative around inflation, and serves as its excuse to overregulate.”

The report’s findings support three primary policy conclusions:

- Trends in industrial concentration should not serve as the basis by which policymakers change the approach to antitrust or regulation. Antitrust enforcement should be based on rigorous economic analysis of competitive conditions and consumer welfare, while regulation should be based on clear evidence of market failures.

- Attacking concentration as an economic policy objective is dangerous as it risks harmful government mismanagement of the free-market and competitive processes that drive economic growth and innovation.

- Trends in industrial concentration do not provide a reliable basis for making inferences about the competitive effects of a proposed merger. Antitrust economists know that market concentration is different from industrial concentration. An antitrust analysis that examines the impact a merger has on market concentration and whether there is resulting harm to consumers is the only standard that should be used to evaluate mergers.

***

METHODOLOGY

The methodological approach is designed to address several issues which have reduced the credibility of previous studies. First, the study evaluates industrial concentration using the narrowest industry definitions available in the Economic Census data. Second, it uses only the most reliable measures of industrial concentration available in the data.

*For the manufacturing sector, this is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which is used by the DOJ and FTC in conducting merger reviews. For all other sectors, HHI is not available, and thus concentration is measured using the four-firm concentration ratio (CR4), which represents the percentage of economic activity accounted for by the four largest firms within a given industry. Third, in characterizing overall trends in industrial concentration, the study considers the entire universe of industries in the Economic Census data rather than selected samples of industries.